Part 2

SUMNER HOUSE

November 18, 1992 - May 5, 1993

February 24, 1993

I'm walking in the vicinity of Sumner House, a converted armory in the Bed-Sty section of Brooklyn, where I've been living for the past three months. It's a bleakly cold winter day and traces of snow and slush are still on the ground from the most recent storm in a seemingly endless string of bitter storms. Even so, the streets are full of skeezers, who dart about poorly dressed but oblivious to the weather. Skeezers are women who prostitute themselves mainly for drugs rather than money. They do their best to make themselves look good, but it just never gels. Some are vaguely pretty, but then they open their mouths to smile and reveal missing teeth. Like everything else about the homeless, these women inhabit a different world, and so their attractiveness can't be judged by normal standards: toothless skeezers are often the most desirable because of their facility for oral sex.

Skeezers walk up to me all the time on my way to and from the shelter, and the pantomime is always the same. They ask for a cigarette, and then a light. Even though I don't smoke, I always carry cigarettes on me because it's easy to make friends sharing them on the streets and in the shelters. So when these women ask for a cigarette, I always pull one out. Once I do, they ask for a light, but they're not really looking for a smoke. The whole purpose of the pantomime is to get you to stop. While you light their cigarette, they ask softly, conspiratorially, "What can I do for your entertainment?"

On occasion, entrepreneurs from the adult entertainment business centered in Times Square hire skeezers, dress them and clean them up as best they can, and put them to work in peep shows and as prostitutes, because it's cheaper to buy them a few vials of crack at two to five dollars apiece than to pay the usual rate.

March 30, 8 p.m.

I glide quietly through snowy Marcus Garvey Boulevard. I've been wondering about the skeezers now for the past month, asking my friend Michael Bell about them. I met Michael here at Sumner House, but he has a different look from most other homeless and I wanted to learn his story. Michael Bell came from a good family, had a college education, and refuses to blame either the system or his parents for being where he is. At one time, he was a diamond cutter making sixty grand a year, and married a woman with two children from a previous marriage. One of her sons got busted for dealing and when Michael went to visit him in prison, the boy suggested that Michael take over his drug business to pay for his legal fees. Michael wanted to show his wife that he loved her son, and by some twisted logic he began dealing himself, but then he also began using drugs, which he had never done before. "That's how my fall began," he told me. In short order, he got busted, went to prison, lost his job and his wife. By the time he came out of prison he was HIV positive. Nonetheless, Michael carries himself well, rarely swears, likes to play chess, and has made a systematic study of homeless life and characters. I've learned more about the system from him than from almost anyone else I've met.

As a result, I know exactly what I'm going to do with my evening and possibly my night.

Now I see her coming. "Would you share a cigarette, brother?" she asks. I stop, pull out a pack from my pocket, and offer it to her. When I casually try to walk away, she asks, "Any light?"

While I'm lighting her cigarette, she whispers, "Any-thing I can do for your entertainment?"

"Yes," I say. "I know a quiet place."

Michael has coached me well. "Stay in your turf," he has advised me, "so that you can control the course of events."

I head for a cheap hotel a few blocks from Sumner House where the room rate is $25 for three hours. Each payday, this hotel becomes a market place; the homeless and street people come here to spend their welfare and Social Security checks. They score some crack, pick up a skeezer, smoke their brains out, and have sex. You could say both sexes get their rocks off, although in different ways.

The room is squalid. The only thing that looks clean is the bed linen, so I sit on the bed, fully clothed. The girl starts undressing herself. She is very skinny but not unattractive. In her eyes is a nameless melancholy, although I sometimes associate this with the homeless who have children but no longer know where they are. I'm extremely uncomfortable with this scene, but I have to look relaxed, as though I have been doing it all my life.

"This is a power game," Michael has told me. "A predatory game. If she figures you're not from the street, she'll definitely take advantage of you. In this game, one always takes advantage of the other. Make sure it's not you."

Yet I discover that it's not so easy to look like someone who doesn't care, who just wants to party, when the entire scene, including this sad, lost soul across the room from me, fills me with dread and even disgust. Michael was ready to introduce me to a "nice" skeezer --"considering that a skeezer can be nice," he added. But I thought that would change the rules of the game. If I really want to talk to a skeezer, to know her and appreciate the whole situation better--because I have an idea of the women the homeless men get their sexual gratification from--I've got to pick her up myself, so that I can experience her rawness as much as possible.

I pull two vials from my pocket and give them to her. A demo has materialized in her hand and she deftly slips in a rock. Cocaine rocks are smoked in a glass tube called a demo or stem. This time she doesn't ask me for a light. Taking a butane lighter from her pocket, she lights the thing herself, takes two deep hits, and passes the demo to me.

"Do I have to ask you to go ahead?" she says, indicating the pipe, which I am holding but not using.

The idea, Michael has told me, is to wear me down. "The more you smoke, the less you'll be able to perform," he said, "which will make life easier for her."

I don't do crack and I don't want to perform, so what's the problem? The problem is how to tell her, without blowing my cover, that I just want to talk, to ask her a few questions, to know her views of the world. And what if she doesn't want to talk?

"What do we do now?" she inquires.

"Why don't you have a seat?" I suggest, looking directly into her glassy eyes.

"What do you want?"

"Excuse me?"

"What do you want me to do to you?"

"Just have a seat. We have nothing but time. Let's get to know each other first."

"You come here to fuck or to talk?"

Instead of answering, I display all the vials I have with me. I am in the middle of what one fellow client calls the "street-shrewd strategizing of sexual intrigue." The girl almost chokes at the sight and sits down.

I hold her hand. "Are you okay?"

"Are you a cop or something?"

"Why do you say that?"

"You're a weirdo, y'know?"

"Because I suggest that we get to know each other first?"

"That's not what usually brings people here."

"I know, but you're special. You don't have anything to fear from me." Her eyes soften. "What's your name?"

"Wanexa, with an `x.' You say `Wanesha,' as in `Natasha.'"

"It's a beautiful name."

"Oh yes," she says proudly. "My father gave it to me."

"Where do you live?" I ask gently.

"It's none of your business."

"I live in a shelter," I tell her. "You know the armory around the corner?"

"Sumner House?"

"Yes. That's where I live."

"I live in a shelter too," she says at last. "Lexington Avenue Women's shelter. They transformed a day-care center into a homeless shelter."

"Isn't this odd? We both live in homeless shelters. That's one thing we have in common."

"I have that in common with 100,000 people in New York City. Big deal."

I give her back the stem and she accepts it happily. "Tell me about your parents," I say.

"What about them?" she asks while putting her clothes back on. "What do you want to know about my parents?"

"Where did they come from? How did they make a living? What are they doing now?"

"They both came from the South--South Carolina and Georgia. Dad worked for the Transit Authority and Mom was a postal worker."

"How many kids?"

"Six," she says between hits. "I was the oldest."

"What happened between then and now?"

"Y'know," she says, tickled, "you sound like a caseworker."

"You know I'm not. You and I are in the same boat. Tell me about your first hit," I say, nodding at the stem.

"My husband, although he was my boyfriend then. It started like a game, but before I knew it, I was hooked. When I look back, I know that was the beginning of my downfall. I've got three kids. They were all taken away from me and now they're in foster care."

"Where's your husband?"

"Surely in jail or in some shelter. I lost track of him long ago."

"Tell me something. If someone were to ask you how he could help you, what would you say?"

"My children," she answers at once. "I want them back. I miss them so much."

"Would you stop smoking crack if that's the price to pay?"

"In a minute."

"May I ask you another question?"

"What?"

"Don't you think that what you do keeps us down, all of us human beings, and puts women back a hundred years?"

She remains silent for a few minutes, weighing the earnest naïveté of my question, then sighs. "The only mistake you're making is to think that I'm still a human being. I've lost all sense of purpose. That's why I live like this. That's why I gave my children up."

A few minutes later, I leave.

There must be a woman for every man, and a man for every woman. Nature planned it that way. Skeezers take care of homeless men's sexual needs. "Is this an accurate statement to make?" I ask Michael Bell when I see him next.

"In a way," he answers. "But remember, it's not a general rule. There are sissies too. For five dollars they'll suck your dick. For ten you can sodomize them."

According to Neil, another resident here at Sumner House, the price of sex on the streets has dropped considerably because of them both. Why pay for a $20-hooker when you can get it for less at home?

April 1

Along with those legitimately down and out, the shelters attract a wide range of social outcasts, undesirables, and just plain hustlers. Ed is a plumber and appliance repairman whose house is in the neighborhood of Sumner House, but who prefers living in the shelter to living at home with his wife and two children. Sounds crazy? When he gets dressed up in the street, he looks like an executive, but he has a terrible weakness for crack, which he chooses to indulge freely. In a shelter he can smoke all the crack he wants; when he's tired of shelter food, when he wants sex, he goes home. He's been married to his wife for 28 years, loves her, and raves to us about how well she treats him when he goes home. He makes good money at his job and gives his paycheck to his wife; she knows about his weakness for crack and gives him enough money to indulge his habit when he wants to. Somehow, it works for them.

Of course, there isn't supposed to be any drug use in the shelter, but the answer to that one is simple. The shelter staff are among the biggest drug abusers I've ever met, dealing crack and ganja freely because they don't have to worry about the police. For the same reason, the shelters are gathering places for homosexuals and transvestites of all races, because the shelter is a good place to see and be seen, to display your wares in a relatively safe environment.

April 15

At 10:30 p.m., I stop at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza just opposite the United Nations headquarters, where, although it's mid-spring, the temperature is in the teens. Twelve homeless men and women live there, some sleeping inside cardboard boxes, some inside makeshift houses--and when I say "houses," you know it's a euphemism. They can survive the cold only because there's a fire burning in an iron can nearby. I had noticed this shantytown a few weeks back when I came to visit a friend of mine at the U.N. I could not believe that there was a shantytown just across the street from the office of the Secretary General of the world body, one of the most powerful people in the world, if only because he is just a phone call away from all the world leaders. This man wants to solve the world's problems, yet he is incapable of solving the simple one right across the street from his office.

I sit down by the fire, ready to spend the night here. It's warm and sweet and I try to make myself comfortable. Human societies look for water when establishing a settlement in the wild; the city's homeless people first look for a warm spot, especially during cold weather. Most of my neighbors are already asleep, but three are chatting while drinking beer. They watch me as I try to find a good spot by the fire. "I'm looking for a place," I explain. "Just for the night."

I assume they will ignore me, but one of them beckons me over with a big hand gesture. "Come on up," he shouts. "Come closer."

I walk up to the trio. The one who called me pulls a can of beer from his pocket and hands it over. "It's not opened," he warns.

"Thank you," I say and sit down next to them.

"Roy," he introduces himself.

"Nouk! Nice meeting you."

I look at the others and shake their hands as they pull them out of their coat pockets.

"Johnny!"

"Bob!"

I have on my thick Siberian coat, of course, but Bobby goes to his own shanty, pulls out a blanket, and places it around my shoulders. "Y'a not prepared for the night," he says and sits down.

I'm warmed by his generosity and gratefully sip my beer. From time to time, a rodent appears, wanders about for a bit, and disappears. I think maybe the animal is looking for heat until Bob says, "These rats are so greedy."

"Give them some bread," Johnny suggests.

"There's no more bread," Bob answers.

"These creatures won't leave us alone then," Roy says. "What time is it?"

"Between ten thirty and eleven," I say. "Tell me, what's the link between rats, bread, and us here?"

"Hey man," Roy answers. "If you need to spend a quiet night here, feed the rats first."

"It's not only here," Johnny adds with a laugh. "It's everywhere on the streets."

There are several delis in the area. I go to look for one that is still open, buy bread and a six-pack of beer. They cheer when I bring the "groceries" back. Each one takes a beer and places it by his side. Bob stands up, takes the bread, and places it around us strategically so that we won't see the rats when they come for a meal. "Now they'll leave us alone," he says.

They keep talking, telling jokes about what happened during the day. At about two o'clock, Johnny says, "It's time to go to the supermarket."

He stands up, followed by Bob and Roy. "Can I come?" I ask, looking at Roy.

"Be my guest."

Johnny goes north, Bob south, Roy west. I stay with Roy, who is older and seems more talkative than the other two. The supermarket, I quickly discern, is the neighborhood garbage can. "It's our turn," Roy explains. "Each night, three of us look for food, aluminum cans and paper to recycle, cardboard for shanties, clothes for all the residents of the colony."

"You're organized."

He laughs. "You can't believe what the guys who live in these apartments throw away every day. While we're starving to death at their doorsteps, these guys throw out tons of food daily. When the sun goes down, we come out. Like rats."

The way he says this makes me crack up because the analogy is dead on. Homeless people compete for the contents of garbage cans with no one but the rodents. "Maybe that's why they provide your `supermarket,'" I say. "They know you're coming."

"I guess so." Roy's innocence is disarming. "People are cool around here. It's the police that give us a hard time."

"How many times have they sacked your shanties?"

"I can't count no more. They come anytime and sack, but we come right back the same night."

"Why don't you go to the shelter?"

"Oh, no! We enjoy our freedom here. In a shelter, we can't come and go as we please. We got nothing against the municipals, but the reason why we avoid the armories is basically the freedom problem. If you want to move into one tomorrow, we won't stop you. Don't get me wrong now, you're also welcome to stay here as long as you want."

He claps me on the back. "And if you buy me beer and smokes, I'll go to the supermarket for you. That's the only thing we don't find in garbage cans. In that sense, rats have it better than us."

We're silent for a few minutes. "Tell me about yourself, Roy," I say finally.

"I'm an electrical engineer. I worked twenty-five years for the Transit Authority. Three years ago, I had an accident. I spent eight months in the hospital and when I came out, no one was waiting for me."

"Are you married? Do you have kids?"

"Oh, yes! A beautiful wife I married out of love and two beautiful children."

Roy is eager to talk about his life. He gives me the impression that he doesn't often get such an opportunity. He explains how his wife "stuck around a couple of months, then gave up" on him. She moved to Connecticut to be with her mother and to save on rent, and she took the kids with her. But up there, she met someone else and forgot all about Roy "the Marvelous."

"That's how she used to call me each time I brought a paycheck home," he says. "It's amazing how who we are and what we do has a lot to do with who we're involved with. It's true, nothing I was or did were for me but for my family. The day I discovered that my wife had left, my drive disappeared."

"Tell me something, Roy. Who do you blame? Who's responsible for your current situation?"

"Me, me, and me. I will not blame my wife, or say that I loved her too much and thought she loved me too. I will not blame the color of my skin, the smell of my breath, or any misfortune--why should I? I'm a white boy from New Hampshire. My father still lives there in a big house. If I thought he was the kind of guy who believes that having a son who doesn't want to pay his rent is okay, I'd go back tomorrow. But I prefer to be here anyway, living the way I live, and learning the true meaning of life."

"May I ask you what you learn?"

"I'm learning to be free of worry. Is my wife going to dump me if I don't bring a paycheck home? I'm learning to be free. Free."

When our bags are full and heavy to carry, Roy suggests that we go back. Johnny and Bob are already there, along with five other men. They look as though they are just waking up. Roy introduces me and adds, indicating the bags, "The boy has a sharp eye. He got all this by himself."

They cheer.

"That's only half true," I argue with a smile.

They cheer again. People start coming out of their shanties as if they know it's time to eat. Two women are squatting and a man is standing, all three urinating in one corner of the same area. They relieve themselves naturally, shamelessly, and no one pays attention to them because they're too busy with the food. Johnny seems to be a tough guy, but his female companion is busy putting aside food for later. She takes all of it back to her `house' and does not reappear.

After we eat, most of the guys go back to the shanties, but Roy doesn't disappear until he makes sure I'm okay. It's already almost 5:00 am and I fall asleep quickly right there on the sidewalk. When I wake up, it's eleven o'clock. Nobody else is awake, so I stand up, stretch, and slip away, heading back to the shelter.

April 23

I met Ralph again yesterday evening and discovered another side of his personality and another aspect of his activities. With me on his tail, he toured his domain the way he did the other night, but this time I learned much more about the underground finances of the homeless. Many of them are on welfare, some bringing in as much as $520 from Social Security and $111 worth of food stamps. Those who are HIV positive or have full-blown AIDS sometimes get $292 as a rent stipend from the Division of AIDS & Services. What they do with the money is their business. They are not supposed to use food stamps for anything except food, but that's like expecting cabbies and waiters to declare all their tips. When they need immediate cash, they just trade $111 worth of food stamps for $70, $80, or $90, depending on where they go and who they deal with. I know several department store owners who offer these desperate guys as little as $50 for $111 worth of food stamps. That's where Ralph comes into the picture. He gives them $100 for the same stamps, as I witnessed yesterday. Needless to say, in this area they all come to Ralph.

"There's a lot of cash to be made here," I told him, "considering that in this area, there are somewhere around 20,000 people, homeless or not, perpetually in need of immediate cash and trading their food stamps for it."

"I agree," he said.

I was a little surprised that he did not dispute the moral implications of what he was doing.

"First of all," he said, "most of these guys don't want to go to the store, so I go for them. Second, I offer them a better deal. Third, they prefer to give their money to me, rather than someone else. Fourth, I take care of them."

"I don't understand that part."

"Stay in touch," he said. "You'll soon find out that we hold a treasury here, in case someone needs help, immediate medical or legal attention. I'm the one they come to first because they know I care. Currently three of our friends are dying of AIDS. We're there for them."

April 30

Yesterday, I finally came to the realization that I am at home among the homeless. This hasn't been a simple or easy transition, and the catalyst has been an extraordinary character named James Terrell. Terrell is a poet, playwright, artist, singer, musician, chess player --he does everything I like to do. What's more, he cares only about making art. Sitting down to play chess with him one afternoon and then looking over his poetry--abundant and filled with spelling errors about which he couldn't care less--I connected with him on a human level. At that moment, I was able to let down my anthropological guard, if only because I am an artist and I like being around artists. Stop your crap, Nouk, I said to myself, and don't make the mistake the Europeans make when they come to Africa.

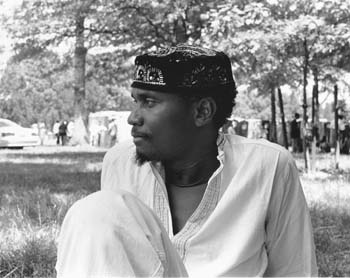

I am the fourth child in my family; James Terrell, born in 1948, is the first of eight children and is the same age as my eldest brother, who became a Catholic priest. Terrell is a big, handsome guy with dreadlocks and, despite a few missing teeth, an air of self-assurance that is absent from most of the homeless. He was so successful dealing drugs with his brother that he used to drive around with plastic bags filled with money in the trunk of his car because he didn't know where else to keep it. After he got busted and did time, he could never get back into the rat race, so he checked into a shelter instead. Now he lives in the shelter system and makes art all day long, cutting pictures out of magazines he finds on the street and creating elaborate collages.

Terrell isn't the only unlikely character I've met in the shelter system. I've encountered a general from Brazil, and a college professor from Nigeria who had fled the military regime there. Occasionally I come across someone from a good background whose apartment has burned down or who's been overcome by a series of catastrophes--losing job, spouse, and home all in a short period of time. But these people don't stay long before they realize they don't belong here--and the other clients let them know they don't belong.

May 1, 2 p.m.

Wanexa's semi-private room at Harlem Hospital is dreary but clean. I can see by the blank look on her face when I enter the room that she assumes I'm coming to visit the woman she shares the room with. I stop by her bedside, take her hand, and whisper, "Do you remember me?"

"Yeah," she says, smiling. "You're the weirdo."

"You checked into the hospital without letting me know?" I joke. "With whom will I chat again?"

She laughs. "What are you doing here?"

"I came to visit you."

"How did you know I was here?"

"We went to Lexington Women's shelter to present one of my friend Terrell's plays. I asked for you and one of the women told me you were here. I told you you're special, remember?"

"If you'd asked me by phone or something, I wouldn'ta wanted you to come. I don't want nobody to see me like this."

She has difficulty speaking because she has deteriorated so much since the evening I spoke with her. "That's exactly why I didn't call," I say.

I give her the roses I have brought her. She smells them and smiles. "I don't know what to do with you," she says.

A tear rolls down her cheek. Because she is too weak, I take back the roses, cut their stems, and put them in a vase with fresh water. Then I sit down in the chair by her bedside.

"Now what can you tell me about you? What happened?"

"I wanted my kids back, so the caseworker insisted that I get rehabilitated," she says, rallying a bit as she relates her story. "I called Phoenix House and they accepted me in their Adult Residential Treatment program. But then the first exam I took, they discovered that I had cirrhosis of the liver. They checked me in here, and I've been in this bed ever since."

"I didn't know you drank too."

"I did everything possible to get high and forget my misery."

Wanexa is clearly in bad shape. I remember her ravaged body when she started to undress in our sleazy hotel room, but I wish someone had prepared me for what I'm seeing now. She looks more wasted away and her skin is pale yellow-gray, an ugly color.

"What are you looking at?" she asks.

"I didn't know that human skin could turn this color," I say innocently.

"Yeah, I know. It's difficult to look at me without staring. It's the end, isn't it?"

"What can I do for you?" I ask almost automatically because there's nothing else to say, and even though it seems plain that there is nothing anyone can do for this poor woman.

"Could you really do something for me?" she asks quickly, surprising me.

"If I can, sister."

She looks me right in the eye. "Get me to see my kids one more time. Even from far away. From this window right here, you can see a playground. Bring them there."

I look through the window at a beat-up, graffiti-painted playground filled with children. "Where are they living?"

She gives me an address and a phone number that I write down, along with their names: Aisha, Malik, and Akeem. I realize that they live right in the neighborhood. "Difficult, not being a family member," I mutter, shaking my head, "but I'll see what I can do."

She smiles and squeezes my hand. "Give it your best shot!"

I squeeze back. A few minutes later, Wanexa is dozing off. When she inhales, I can hear a small moan, and when she exhales, a longer moan. I heard this same noise twenty-six years ago, when my older brother was dying of tetanus at the age of sixteen, and I've never forgotten it. On my way out, I meet a nurse.

"How bad is she?" I inquire.

"Are you a family member?"

"Of course."

"Her liver has turned into a piece of leather. It doesn't function any more. So the kidneys have shut down, causing cardiac exhaustion and peritonitis. The collapse is systemic. Fluids are building up-- that's why her stomach is swollen."

"Can I ask a difficult question?"

"It depends."

"How long before the end?"

"Do you mean how much time does she have to live?"

"Yes."

"Will you keep it to yourself?"

"Yes."

"Anytime. Anytime."

May 2

At one o'clock in the afternoon, I show up at the address where Wanexa's children live. It's a Sunday and I figure the family should be home from church. The foster parents, a man called Musa and his wife, Alema, listen to me silently.

"She just wants you, or me, if you trust me enough," I say, "to bring the kids to the playground behind the hospital so that she can see them through her bedroom window for the last time."

Musa clears his voice. "We'll do better than that," he says. He calls, "Aisha! Aisha!" An eight-year-old girl appears. "Get your brothers dressed. We're going to the mosque!"

"But I thought," the girl argues, "that it wasn't till the evening."

"We will stop at the hospital to visit a friend, sweetheart," Musa explains. Pushing Aisha toward me, he adds, "Say hello to the brother."

"As-Salaam aleikum," she says shyly.

"Aleikum Salaam," I reply.

"Let me bring you tea," Alema says and stands up.

"I have to tell you, my brother," I say, "that she doesn't want anyone to see her dying, especially not the kids."

"Death is part of life, my brother. And this is an act of love and affection. The kids will learn from it."

I'm moved by his quiet statement and know he is right. Whether it comes from his religion or his own experience doesn't seem to matter. Still, we agree that I will go ahead of them to prepare the way. I sip my tea quickly and leave.

When I get to the hospital room, Wanexa looks different--better. She has just come from her bath, helped by a young friend from the shelter who is also fixing her hair. "You look beautiful today," I say. "Are you going out?"

Wanexa barely smiles at my joke. I have to talk more than usual and try to tell jokes--something I'm no good at--to keep her light-spirited. Precisely at three o'clock, Musa and Alema burst in with Wanexa's three kids and two of their own. This explosion of youthful chatter and laughter injects some much-needed life into the room. Wanexa looks stunned, but happily so. She looks at me, but I am already on my way out the door. It's perhaps the best moment I've had in my brief relationship with her, and her life is almost over.

May 6

My sojourn at Sumner House has come to an end with a tragi-comic bang. The court has ordered a down-sizing of the shelter and the first target is Terrell, who has been serving as editor-in-chief of the Sumner Gazette, an in-house publication that has taken upon itself to "kill the imperfections of the community that's Sumner House and the shelter system at large." Residents have been very supportive, but today they keep a low profile. Sumner House is purging its undesirables and no one wants to share the fate of the Sumner Gazette's editorial staff.

"I've been transferred to Harlem I," says Terrell, storming into the Life Management Center, a security guard on his tail. Cynthia, the office's director, is speechless. "These guys have been in the Gazette's newsroom and have smashed all my work down," he continues. "My art is destroyed."

Having just come from there, I've already seen the damage. On July 4th, 1976, when thirteen Cameroon-ian police with assault weapons stormed into my room and sacked the premises before arresting me, it looked quite similar. "They have something against you," stammers Cynthia. "It's intolerable."

She stands up and walks out with Terrell as the guard dutifully follows, but I have seen this coming. A week before, a guard told me, "You guys are getting bigger every day. What will happen to my job if there's no more homelessness?" I even predicted that the Administration here would use this downsizing as a pretext to konk Terrell and his friends on the head. Did Sophocles tell us everything when he wrote "Truth is the best argument"? He should have warned us of its danger. Ten minutes later, Terrell is gone.

In the course of the next three days, all of Terrell's friends are made to leave, including me. I don't regret this. On the contrary, I am still happy for the seven months I've spent here. But why stop at throwing us out of Sumner House? We should have been thrown out of the international system. Out of the planet. Homeless people are the American nightmare. They represent the hard core of what America does not want to see. And now I'm beginning to be part of that hard core, even though I still have a home that I can return to if I choose. I have begun to feel the weight of contempt that is projected by the staff in these shelters toward the homeless. This is complicated by my knowledge that the staff workers don't have anywhere near my level of education, my level of income potential, or my understanding of the world, yet they are treating me like shit--and I have to take it! Moreover, I know that if I were to tell the Nigerians on staff "Hey, brother, I'm from Cameroon" (although I have an accent, it's usually taken for Haitian), or if I were to say a few words in Yoruba or Pidgin, the way they relate to me would change completely. Yet I have to stay true to my goal of discovering the secret of the shelter system, and so on some level I remain an observer, as infuriating as that role can be at times.

FRANKLIN SCCM

May 9 - September 29, 1993

May 9

When I walk into the Franklin Shelter Care Center for Men in the Bronx (Franklin SCCM), it is 1:30 in the afternoon.

"Hey, we don't accept walk-ins," a worker sitting behind a desk shouts, trying to stop me. These guys make me tired sometimes. I look at him that way, to let him know that he is tiring me.

"How do you know I'm a walk-in? Just by looking at me?" I ask, speaking very slowly. He doesn't have the reply to that. I walk up and hand him a transfer.

"Coming from Sumner?" he inquires.

I nod, showing the sheet of paper. "Obviously."

"Go up to Social Services, second floor."

The woman on duty doesn't cause me any trouble. She has a beautiful face but her lower body is extraordinarily large. She gives me a meal ticket, assigns me a bed. "Mr. Lassiter is your caseworker," she says. "He'll be here Monday. You can see him then."

I head for the recreation room, but as I walk in the recreation director stops me. "You can't come in unless you want to attend the Interfaith meeting," he says.

"Of course," I reply. I don't know what the hell Interfaith is or what their meetings are all about, but I need to sit down and cool off a little because I'm feeling pissed at being made to jump through yet another hoop. When I walk in, a dozen people are already inside and the meeting has just started. Three white nuns in civilian clothes look very much in charge. As soon as I sit down, someone hands me a Bible, which strikes me as odd right off. I mean, if this is an Interfaith meeting, why assume that I'm Christian? Because of the way I dress, I'm often mistaken for a Muslim, so if anything, I ought to be handed the Quran. But I could just as well be a Buddhist or a Vedantin. For two hours, the participants talk about God, the Gospel, and their personal relationships with God. I've heard all this a million times, so I barely listen until Sister Teresa, who is presiding over this gathering, asks me to talk. Now I'm only too happy to get a few things off my chest.

"The problem I have with the Interfaith movement," I say calmly, "is that the only holy book made available in your meetings is the Bible. Is this another Christian scheme, talking about Interfaith but really fostering Catholicism? Don't you see that in doing so you insult people's intelligence, and that each time you insult people's intelligence you really insult your own? What do you wish to accomplish with this kind of scheming?"

I'm on a tear and Sister Teresa has to stop me. "Listen, my friend," she says, cutting in, "no one keeps you from bringing whatever book you wish to these services. We'll discuss any passage you choose."

"It's not for me to bring the book I wish to discuss," I reply with an edge of annoyance. "You should bring it, just as you brought the Bible. Each time you organize an Interfaith meeting, you should make all the holy books available and discuss all of them at each gathering. Then you'll truly be Interfaith."

Sister Teresa, a good moderator, decides to stop the discussion. "In a way," she says, "you're right. Next time, we will make sure that the Quran is available."

"Bring the Dhammapada also," I say, not wanting to let her off the hook.

She smiles.

"What's the Dhammapada?" asks a man sitting next to me.

"The sayings of the Buddha," I reply.

After the meeting, someone brings out cakes, tea, and coffee and we all socialize like old co-religionists. If the group is shocked or offended by my remarks, they don't show it. Food conquers all.

Dinner at Franklin is from 6 to 7, but I eat very little because of all that cake. Instead, I sit in the dining room observing the residents, an especially raw crew, even more so than at Sumner House. In fact, they remind me of Atlantic Shelter clients: the same rush to get the food, the same yelling, shouting, trading food. Most wear torn clothes and some stink strongly.

After dinner, I go back to the sleeping area to find the bed assigned to me, A37. Franklin SCCM is nothing but another ugly armory-turned-shelter, and the sleeping area is on the drill floor, with 600 beds in it. Another day, another bellyship. Two residents named Harry and Malik come over to me and announce that they were at the meeting and liked what I said. Harry holds the Bible in a way that identifies him as a Christian ready to quote chapter and verse. Malik, who is very dark-skinned, wears the white skullcap or kufi of the devout Muslim. They are good friends and yet they always seem to be arguing, like two guys on a radio talk show. All they agree on is what they have in common--the fact that they are African Americans. The discussion lasts an hour and then Malik excuses himself and Harry proposes to show me the joint.

I follow him upstairs to see the other sleeping areas, starting with the Veterans' dorm on the second floor. The third floor can sleep a hundred people, the fourth, twice that number. On our way down, I inquire about lockers. "Just pick one that's empty," Harry says. "Put your stuff inside, a lock outside, and it's yours."

"Generally lockers go with beds," I observe. "Locker 34 on the drill floor should belong to the one sleeping in bed 34."

"That's how it's supposed to be," he says. "But you know, in the system it don't work that way. The system does not work at all, I might add."

It's 10 o'clock by now so I put my stuff in a locker, get linen, and make my bed. Then I lie down and crash almost immediately, exhausted, as often happens, just from the effort of finding a place to sleep. An hour later, I am awakened by a naked Puerto Rican who is walking around and calling his countrymen to arms.

"Secession! Secession! Los Americanos diablos!"

Despite my weariness, this scene brings a smile to my face for the first time that day. But since I can't go back to sleep, I use the bathroom, then come back and lie down on my bed. If the drill floors in these armories are designed like bellyships, I wonder, where are the shackles? After a few minutes of rumination, I discern them in the bed roster all the residents are required to sign every night between 9 and 10. This is how the master--here the system--knows where his "slaves" are.

"Fuck this shit!" I say to myself and I leap from my bed and start packing. I'm ready to quit the system for good. The lights went out at 11, but even so it's still bright enough to see clearly. As I sit on the edge of my bunk planning my next move, three clients converge on a vacant bed next to me. They have on dark catsuits that make them look like ninjas--very hip-hop. One of them seems familiar but I can't place him. Oblivious to me, they sit down and begin to talk, not loudly, but not whispering either.

"Keep it cool, man," says the first one. "No fanfare. No flowers. No nothing. A casket. That's it."

"Come on, man," argues the second. "When Billy Martin died, people clapped. That's hip."

"Billy Martin was a baseball legend. You ain't. The nigger was known all over the world. Who knows you?"

In this milieu, I realize, the word "nigger" means something different. With some dismay, I also realize that they are planning their own funerals, although they can't be more than twenty-five years old. I quietly lie back down, put my left arm over my eyes, and feign sleep, wanting to hear the rest of this bizarre conversation.

"I want my friends to remember me as bad," insists the second one. "Bad! I don't want my sister to cry. When women cry, you don't look like you were really bad. If women cry, I want them removed!"

"Flowers," says the third one. "Lots of flowers. Like a don. A capo. That's me!"

I'm thinking this kind of dialogue belongs in a screenplay. As I work to fix it all in my memory, the guy who spoke first segues out of the funeral rap.

"Are y'all ready for the mission tonight?" His tone is more serious than before. Involuntarily, I hold my breath.

"Yeah," says the second one. "Always ready for some action."

The third is already on his feet. "The bitch gonna suck tonight," he says with an air of bravado.

I start breathing fast.

"It's gonna be hour `H.' Let's go!" the first one orders. Without thinking, I sit up abruptly.

"Can I come?" I ask. They spin around as a group, noticing me for the first time. "Come on, boys," I argue. "I can't sleep in this fucking shelter tonight. Need some action too."

"We won't be bothered by you," says the first guy, who is already walking toward the exit.

"Listen, man," pleads the second one, "he might be some help."

This one, who I feel I've seen before, seems to be the leader. He tells me that they planned on recruiting two other guys in this shelter, but the ones they had in mind are missing. If clients use the shelters for sex and drugs, outsiders use the shelters for other reasons. When the cops need to fill out a police line-up, they come to the shelter and offer residents $20 apiece to stand in--and the clients come running because they know it's easy money. When the local drug lords want to teach someone a lesson, they come to the shelter and hire a few of the tougher guys to do their dirty work dirt cheap. The shelters are human warehouses stocked with cheap labor desperate for money. These three guys have come here looking for some backup.

"So why not him?" the second guy is asking his friends. "He's smart."

"Don't give a fuck whether he's smart or not," interjects the third. "Is he cool? That's what I want to know."

"Yeah, the man's cool," says my sponsor. "I know him from Sumner." Looking at me, he asks, "You wrote in the Gazette, right?"

I nod, and that seems to be enough for the others. A few minutes later, as we're driving, they introduce themselves. Jamal, the one who knows me from Sumner, and Akeem are both tall and strong, but Kadeem is shorter and built like a bull. He drives and they insist that I sit next to him.

"I'm Nouk," I say. "N-o-u-k. Not N-double-O-K. Nouk. Simple."

"All right, Nouk," says Akeem.

"The brothers raised hell at Sumner with their paper," Jamal says with an appreciative laugh. "They had to kick their butts out." He is speaking more to his companions than to me, but I smile too. "We spoke the truth," I say.

"According to the Scriptures," says Akeem, "he who speaks the truth raises hell."

"That's how he knows that he's speaking the truth," says Kadeem.

"Where are we going?" I ask after a while.

"We're on a mission, my brother," Akeem answers. "We'll let you know when the moment comes."

"Tell him," Jamal says.

"You tell him," Kadeem says.

"We're with an organization called the Brotherhood of Reconciliation," Jamal says. "We work for peace and understanding among the people, all the people, especially the American people--"

He looks at me. "I'm listening," I say.

"Tell him about the mission," Akeem says.

"We've got to teach a lesson to some girl," he replies evasively.

"Anything kinky?"

"Not at all," he says with a laugh.

"Seriously?"

"Seriously. You know we're not into dirt."

A hint of firmness in his voice makes me believe him. We drive for about twenty minutes. At one point I notice that we are entering Westchester County. Five minutes later, we stop, cut all the lights, and wait. I have several questions but think it best to keep my cool, wait, and see. A few minutes later, Kadeem looks at his watch. "It's about time," he says.

He places his right hand on his heart and his friends follow suit. They recite something that sounds like a cross between a prayer and an oath of allegiance, then they all don gloves and dark glasses and resume their vigilant posture. Five minutes later, a car stops across the street. I watch as a white girl gets out on the driver's side and walks toward an apartment building. In a flash, my three companions bolt the car and accost her, Akeem wrapping his hand across her mouth to prevent her from crying out. She struggles briefly but is no match for their size and strength. The next thing I know, she's pinned between Jamal and Akeem in the back seat and Kadeem is driving like a madman to get away from the area. The whole thing has not taken more than a minute, but that istime enough for me to understand that "teaching a lesson to some girl" has turned into a kidnapping. I am part of a kidnapping, which, as far as I know, is a federal offense and a capital crime. What could I have been thinking?

Kadeem drives to a neighborhood I don't know. I turn to see what's happening behind me. Jamal's hand is now over the girl's mouth. Her eyes are wide open, and for a brief second we make eye-contact. I'm sure she can read in my eyes that I too am wondering what's going on and what's wrong with these guys. Like it or not, we're in this together.

Ten minutes later, we pull into the driveway of a suburban house and continue into the attached garage. It's a well-to-do white neighborhood where we would stand out if we were spotted, but we go right from the car through a doorway and into the basement, which is filled with furniture in storage and a large bed. Jamal pushes the woman onto the bed, and she sits there looking terrified. I sit down and pull my note-book from my pocket, which nobody seems to mind. The young woman, as I soon find out, is an executive of another "reconciliation" group, but her organization specializes in worldwide reconciliation whereas the Brotherhood insists that reconciliation start at home. That seems to be the crux of the problem. The kidnapping is part of some larger political turf war, although I have no clear idea of the size and extent of the opposing groups.

I look at the woman--let's call her Josephine. She can't be more than thirty. "How did you get to know her?" I ask Jamal.

"She advocates reconciliation at all times," he says, not answering my question. "What's scandalous is that the girl wants to demilitarize Somalia and Bosnia, but not the streets of America. She couldn't care less about what goes on here."

"She wants to feed the hungry of the world," says Kadeem, approaching the bed threateningly. "Clothe the needy of the universe, but not the hungry and needy of America. This will stop!"

He is seething. Of the three of them, I fear Kadeem the most; he is the calmest on the surface, but I've noticed that the calm ones are often the most unpredictable. When they explode, they may go too far. "Unbelievable!" I write in my notebook. "Kidnapped in order to be taught that reconciliation starts at home!"

May 7

I wake up at around 1 p.m. Kadeem is the only one up, since he has been on guard duty for the last three hours. Josephine, worn with fatigue, has finally crashed.

"Is there a bathroom in this house?" I ask Kadeem.

He points a finger upstairs. I thought at first that the building was abandoned, but as I walk into the bathroom, I am surprised to discover that it's every bit a middle-class house, with an impeccable and well-appointed bathroom. When I go into the kitchen later to make some coffee, I find everything I need, including some high-priced beans and an electric grinder. I make a full pot, pour out two cups, and bring one down to Kadeem.

"I don't drink coffee," he says. "Tea only."

Sitting down, I realize that there's no daylight in the basement. "It's a beautiful day," I whisper to Kadeem. "You can see it from upstairs. It's unfortunate that we can't see the sunlight from here."

"Why don't you go outside then?"

"I prefer to stay here."

"You want to keep an eye on the girl, right? You afraid she might be raped?"

That has crossed my mind. "Are you capable of raping a woman, Kadeem?"

"Only as a punitive action," he replies. "To teach her something."

Isn't that usually what's implied by rape? Akeem comes downstairs with a steaming cup of coffee in his hand, complimenting its maker. "That's Italian style, man," I say, trying to lighten the mood. "Italians know how to make coffee."

Jamal comes down an hour later and asks Kadeem to fix us something to eat. "Why do you stay down here when the whole house is empty?" I ask Jamal.

"Where should we be?"

"The living-room is spacious and we could be enjoying the daylight, man."

He smiles, shakes his head. "Five people in the house would attract the attention of the neighbors. Usually only one person lives here."

For a revolutionary, he makes good sense. Roused by our voices, Josephine opens her eyes. I can see the fear return to her a little at a time. Someone in her situation thinks at first that she is just waking up to a new day, but then it gradually dawns on her that she doesn't recognize the walls, the bed, the smell of the place. For a split second, she thinks that she is still sleeping and having a horrible nightmare. Slowly, she comes back to reality and convinces herself that it's not a nightmare--but then comes the realization that it's all too real. What she needs at that moment is a word of encouragement.

"Good afternoon," I say brightly. She doesn't reply. "There's a bathroom upstairs."

She looks at Jamal. "Take her to the bathroom," he says to Akeem. Josephine leaves the room, followed by Akeem.

"How is it going so far, bro?" Jamal asks me.

"It's for me to ask you that question," I say. "You know very well that I don't condone your methods. There are many different ways to get a message across."

"We've picked this one. You see, what I like about you being here is that you can witness something different. Action. Not writing. You can also see our reality from a different perspective."

"Our? Have you said `our'? Who are you talking about when you say `our'? Are you talking about homeless people? The disenfranchised? Minorities? Black men? Who are you talking about?"

"All the above. There's something you haven't understood about America, and you won't get it unless someone or something puts you in a situation to see it."

"What's that?"

"You don't have any idea of who's really angry in this country, and how many they are. You'll be surprised, my brother. Our perspective is the perspective of the angry. It's not a black or a white thing."

"What do you wish to accomplish?"

"Little changes. Here and there. One at a time."

Josephine returns in the middle of this conversation.

"You have a long way to go," I say to Jamal.

"Of course we have a very long way to go--that's why we don't have time or energy to waste. And we need all the help we can get."

"Now tell me how actions like this one help your cause."

"You see, my brother, there is weakness in strength, but there is also strength in weakness. We are weak, yet very strong because we turn our weakness into strength."

"To me, you have the same agenda. Reconcil-iation. Yet this young lady here might hate you for the way you're treating her."

"How are we treating her?"

"What do you mean to accomplish by threatening her?"

"We're doing her job, don't you see?"

"Offer her some coffee, man."

"She can go get some her damn self. Where does she think she is, the plantation?"

"Bring her some coffee, Pap," I insist.

Jamal goes out and brings back three cups of coffee on a plate and Josephine takes one. "That's Italian style," I repeat, "made especially for the enjoyment of your highnesses by your humble servant."

My humor is crude but sufficient to eke a smile from Jamal, if not from Josephine. At least he has indicated that she's free to move around the house. Has she noticed it also? I think so, because when I make eye-contact with her she looks a little less fearful.

That evening, we have dinner with beer and go to sleep without further conversation or incident.

May 8

Jamal appears at around 11 this morning. The ninjas still have their dark glasses on for full effect, and I have to wonder how they can see at all in the lightless basement. Jamal has a cup of coffee in his hand and is holding forth with a philosophical discourse on the need for reconciliation in America. He reminds me of a young Stokely Carmichael.

"Everything is dying a slow death," he says, while I jot down notes in my pad. "Who will give us another shot in the sun? New waves like rap and hip hop, ain't doin' shit. Look at who controls it. It's too depressing to even think about it. The only place I'd like to take the angry is the brain place. I'd like to print signs everywhere with `Stop at the Brain Store' on 'em. Sometimes fun-time can become a lifetime of misery. A permanent short-circuit. `The world owes me. America owes me.' That's all I hear around me all the time. I mean all the time! I say, with that belief, you wait for everything to be handed to you on a silver plate. It's a wrong idea, a very wrong idea for us, especially the younger generation, to keep thinking that America has done us wrong and that she'd better apologize and pay reparations before we proceed and do something for ourselves.

"I've been in the shelter system. As a matter of fact, I'm still in the shelter system. I have an H.H.R.A. number. Here's my meal ticket. Listen, man, the shelter system thinks that to make me happy, all I need is three square meals a day, eat catsup soup, stick cardboards in my shoes and wear a frayed woolen coat from the shelter's thrift shop. Punks deserve love, too. Coming up with solutions is the hardest part. What are we going to do? Life gets stormy for the angry that are trying to fit into a world that moves too fast..."

While Jamal is rapping, I observe Josephine, who seems moved by his words. As he rattles on, something changes in her eyes. The fear gives way to understanding, perhaps even compassion. "We all open our eyes every morning in a world that's cruel to us," she says suddenly. "But at least it's a familiar world. What we've got to do now is create a bond that makes people strive for something worthwhile, making it better for all."

I don't know whether she is speaking to Jamal, to all of us, or just to herself. She says these words with no anger in her voice, even seeming to espouse Jamal's view. I like what I'm seeing: American youth talking to each other about themselves, their place in American society, and especially the future they have to build together.

"--a world that seems to go fast, too fast," is Jamal's main concern. "How to fit in it?"

"Create a bond that makes people strive for something worthwhile. Make it better for all," is Josephine's answer. Reconciliation at home for Jamal, reconciliation in the world for Josephine. Jamal does not feel safe in the streets of America. Josephine does not feel safe in the world. Where do they meet? Will they ever meet? Jamal doesn't care about world safety. Josephine doesn't know the streets of America. All she cares about is the world's safety because she likes to vacation in Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya. Should all the Jamals of America make sure that all the Josephines of America know the streets before going to make peace in the world. By any means necessary? Is that the message here? Is this the only way to make the present, but also the future, better for all?

Something has happened in the room and the tension drops afterwards. Josephine has become one of the group. Jamal realizes that she understands him and she feels that he knows it. "I'd like more coffee," she says a few minutes later.

"This time, you'll go get it your damn self," Jamal says. "Where do you think you are--"

"A plantation?" Josephine says as she disappears up the stairs.

I laugh. When she doesn't come back right away, we go looking for her and find her fixing lunch.

May 9

The ninjas have left. They just packed their stuff, said "We're out of here," and walked out the door. Josephine wasn't ready so I stay behind in case she needs a hand. I wait while she goes to the bathroom-- and comes out two hours later, looking different, beautiful, with clothes she borrowed from one of the closets. From some leftovers in the refrigerator, she fixes two sandwiches, bringing out a bottle of red wine I'd noticed before. "What do we do now?" she asks.

"We have to get out of here, too," I say.

She stands there for a couple of minutes and suddenly breaks down, sobbing hysterically. After keeping herself under control for three days, she breaks down completely. I offer her my shoulder. "Where are we?" she asks after calming down.

"To tell you the truth, I don't know," I say. I feel compelled to ask why she cried.

"Nothing like this ever happened in my life before," she says.

"I thought it was because you're happy to be free again."

"I thought they were going to kill me," she says.

I hold my breath. "When exactly did this idea cross your mind?"

"Last night."

That's a surprise, since last night they had a mini-party here. The ninjas brought over three women they introduced as their girlfriends, and disappeared with them from time to time, reappearing only to drink a beer or smoke something. This lasted until four in the morning. I think Kadeem took the girls home later, but I'm not sure because I crashed. "When did this happen exactly?" I ask again.

"I thought that they were going to stop me from talking."

"They'd pay you to talk, believe me," I say gently. "To tell you the truth, I would love you to go to the police and report this kidnapping. I'd love to be a key witness in this case. No one should resort to this method to get a point or a message across. It's violence. With the publicity, media coverage, a lot of people will identify with the case. Few people in America today can say that they are not afraid to go home at night. The streets are a militarized zone-- kids killing kids, kids planning their own funerals because they know that they don't have the time to live. What kind of society is this? Press charges and make it public."

As we leave, Josephine is still thinking about all this. I call a cab to take her home and then I catch a bus to the shelter.

HARLEM I MEN'S SHELTER

September 29, 1993-February 28, 1995

September 29, 1993

As I walk into Harlem I Men's shelter, Terrell, seated at his usual place in the rec room just facing the entrance, raises his eyes. He stands up and walks over to me with a big smile. "It looks like you've been transferred here," he remarks.

"I told you I wouldn't stay away from you for long," I say.

We laugh. He has been making art, so we walk to his table and he shows me his latest pieces. It's around 11:30 and lunch time is approaching. Since I need a meal ticket to be able to eat here, I go to Social Services. The caseworker who receives me is Mr. Albert Sarmah, a native of Liberia. I wonder what's become of the Nigerians.

"Nothing is supposed to happen here," he begins. "You see it as you come. Harlem I is different from any of the New York municipal shelters. First, it's a school-turned-shelter, not an armory. Homeless Facilities considers it its showcase--if the Pope or the Queen of England stops in New York and wants to visit a homeless shelter, this is where they'll be brought. So you'll be transferred in a minute if you start trouble."

The man is right. Nothing happens in this shelter-- literally. With a high level of employability, Harlem I does not even look like a shelter. There is a vending machine visible from the entrance. Floors are mopped twice a day. One hundred fifty clients reside here at the moment, of which one hundred twenty are currently employed or undergoing some kind of active training. They don't even look like homeless people. In one sense, I feel like I've moved up in the world of the homeless. In another, my interest level has already begun to decline. There will clearly be less idiosyncratic behavior here, so I settle in for the long haul.

February 28, 1995, 10 a.m.

When I walk out of Harlem I Men's shelter almost a year and a half after moving in, I am through with New York municipal shelters. I am the first to wonder how I was able to live so long in this shelter where nothing ever happens, but no matter, because now I'm ready to enter the next phase of my exploration of homeless life. I have nothing more to learn from the shelter system, so this coming spring and summer I will live on the streets. All my belongings, my books, my music, my clothes, everything I brought from Paris, are still in storage in the sculptor's house in St. Albans.

Homeless people who live in shelters are not truly homeless. Bad as the shelters are, clients still have a roof over their heads, three square meals a day, a bed. Their linen is changed every week, they have running water, soap, heat. I've already been initiated into true street life and the world of the Mole People by Ralph, but now I'm prepared to join them myself.

EPILOGUE

April 1, 1996

I've been living on the streets for nearly a year, although on winter nights I have been able to stay at the apartment of a friend and use a computer there to complete my journal, of which this excerpt is only a small fragment. When I decided to leave the shelter system, it was because I felt that I'd accomplished what I set out to learn. I had become the homeless woman I saw lying on that street corner two and a half years before. Back on that cold Election Night in 1992, I thought of myself as a hotshot radical, someone trying to fight governments while at the same time running around to political meetings and parties, hanging out with the rich and famous. Now I realize that without knowing it, that dying woman, whose fate I was never able to learn, initiated me into the next part of my journey. What she said to me that night, in effect, was that I wasn't applying the teachings of my Bassa elders. I'd been living on the surface and not diving into the depths of things. As a result, I'm a different person now than when I met her. I no longer want to own a house. I don't even want to go back to Queens to live in a friend's home.

I began my journey by asking myself why somebody would prefer to freeze to death on the streets when she could have gone to a shelter and been given food and a warm bed to sleep in. I got the answer to that question by experiencing the humiliations and frustrations of living in homeless shelters and then sleeping on the street myself. By living in the street, I have experienced my own liberation from the obsessive needs of civilization. This is my path for the foreseeable future. I don't recommend it for everyone, any more than I would recommend a life devoted to asceticism in the caves of Nepal, or serving the lepers of Molokai. But it's the life I lead now.